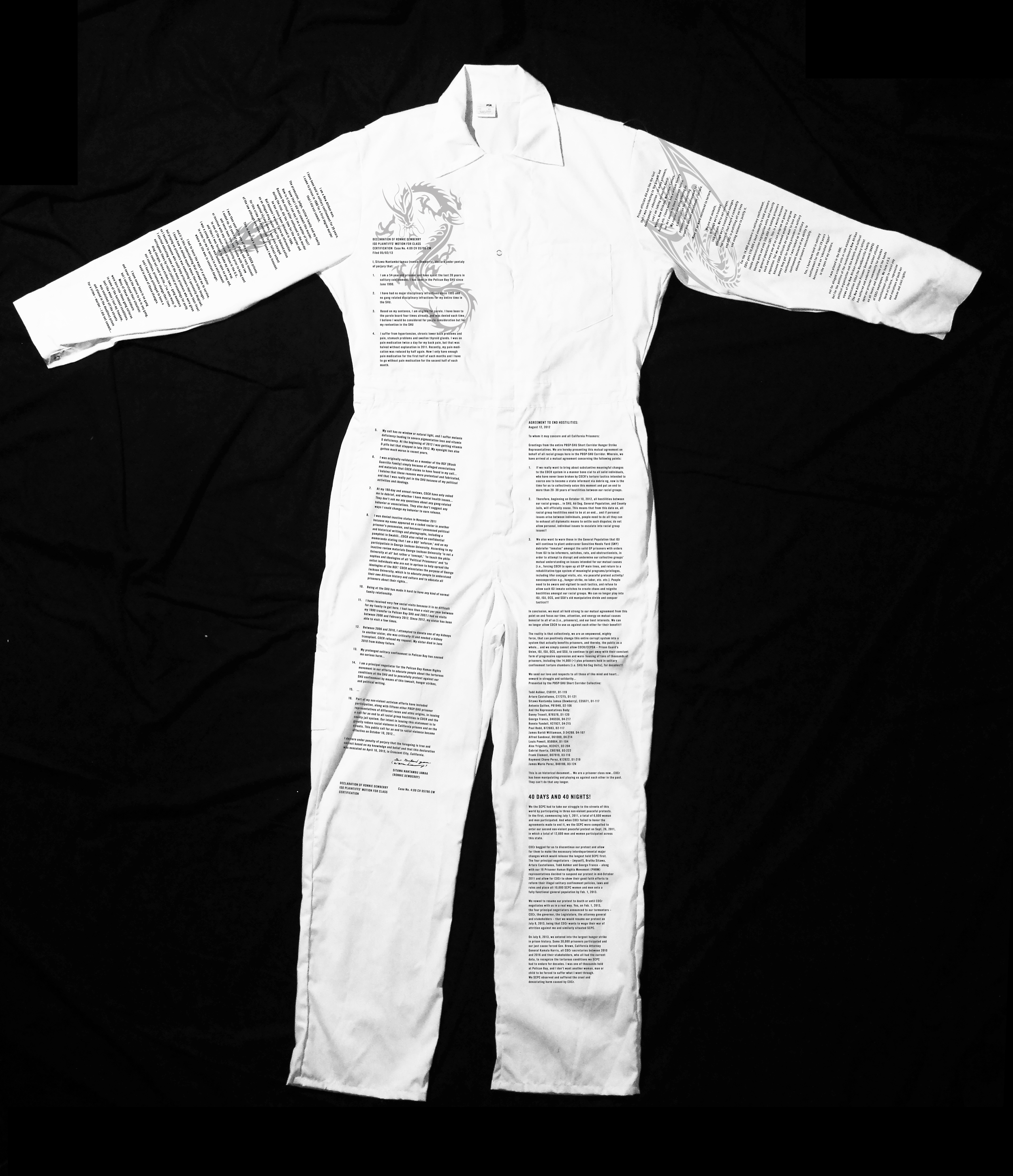

social death

“Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.” 8th Amendment, US Constitution.

The Supreme Court declared in 1978, “[c]onfinement in . . . an isolation cell is a form of punishment subject to scrutiny under Eighth Amendment standards,” yet the court has avoided a definitive ruling on the question. In prisons, Indefinite, long-term solitary confinement is used as a form of extra-judicial punishment or in lieu of mental health care. UN Special Rapporteur on Torture Juan E. Méndez has denounced the use of solitary beyond fifteen days as a form of cruel and degrading treatment that often rises to the level of torture. Yet the United States holds more than eighty thousand people in isolation on any given day.

Far from being a last-resort measure reserved for the “worst of the worst,” solitary confinement has become a control strategy of first resort in many prisons and jails.

Today, incarcerated men and women can be placed in complete isolation not only for violent acts but for possessing contraband, testing positive for drug use, ignoring orders, or using profanity.

Today, incarcerated men and women can be placed in complete isolation not only for violent acts but for possessing contraband, testing positive for drug use, ignoring orders, or using profanity.

Recent studies have shown that people of color are even more over-represented in solitary than they are in the prison population in general, and receive longer terms in solitary than white people for the same disciplinary infractions.

Individuals are sent to solitary based on charges that are levied, adjudicated, and enforced by prison officials with little or no outside oversight. The most recent national data available shows that 80% of prisoners held in solitary confinement are people of color.

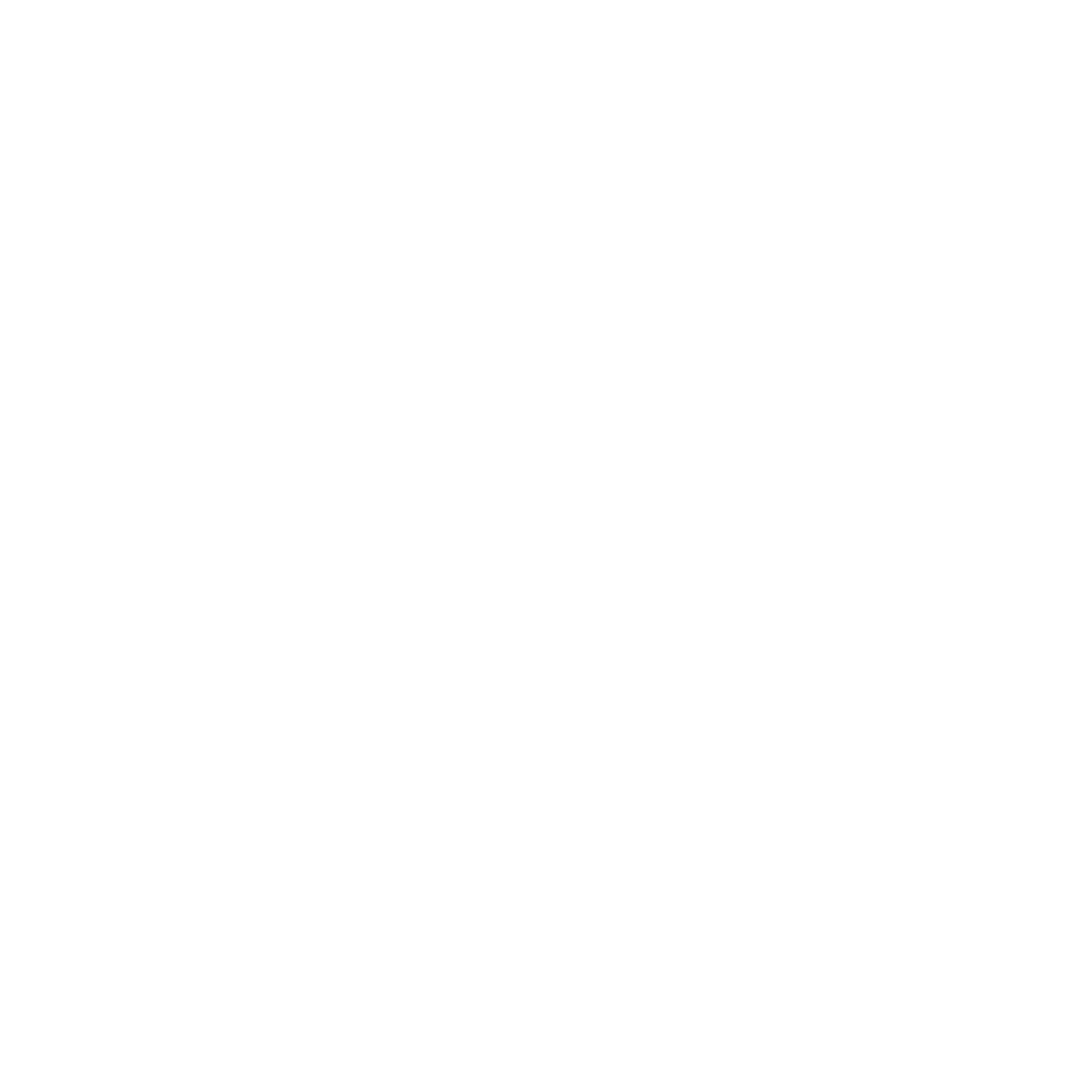

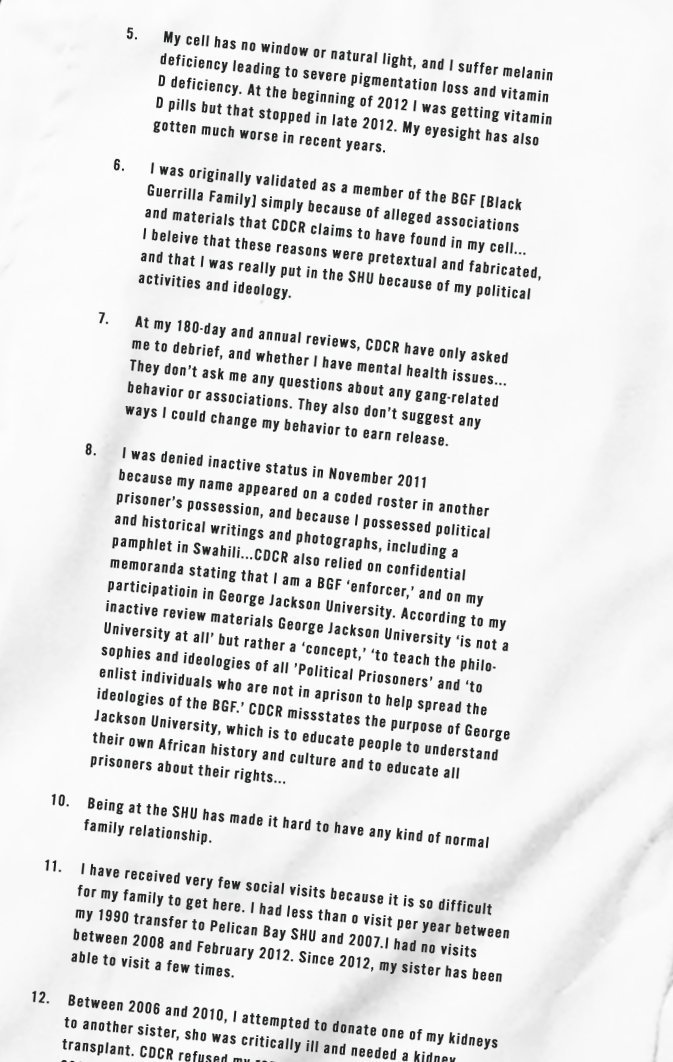

Prisoners in Pelican Bay State Prison’s Security Housing Unit (SHU) are isolated for at least 22 ½ hours a day in cramped, concrete, windowless cells. They are denied telephone calls, contact visits, any kind of programming, adequate food, and often, medical care. Nearly 750 of these men have been held under these conditions for more than a decade, dozens for over 20 years.

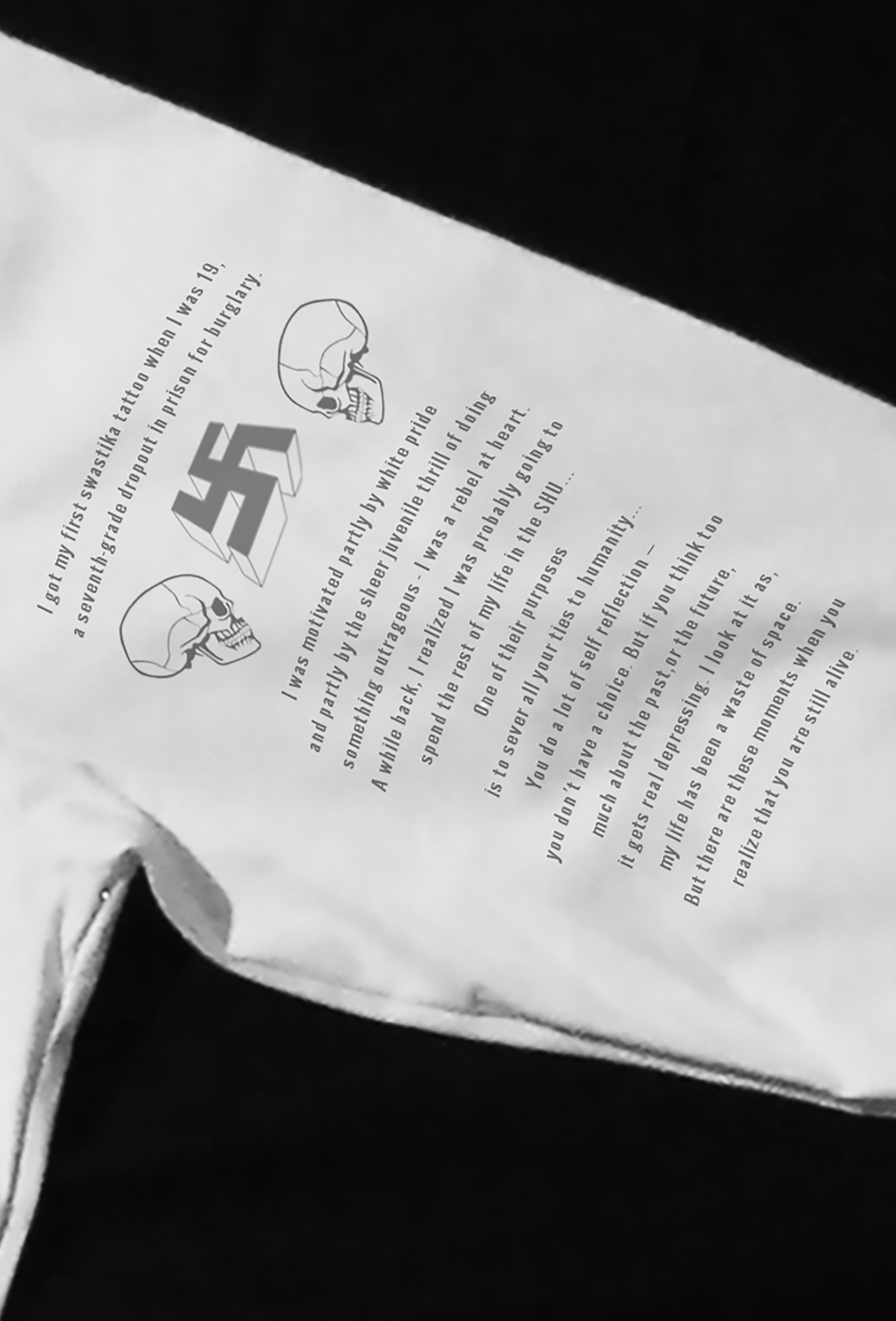

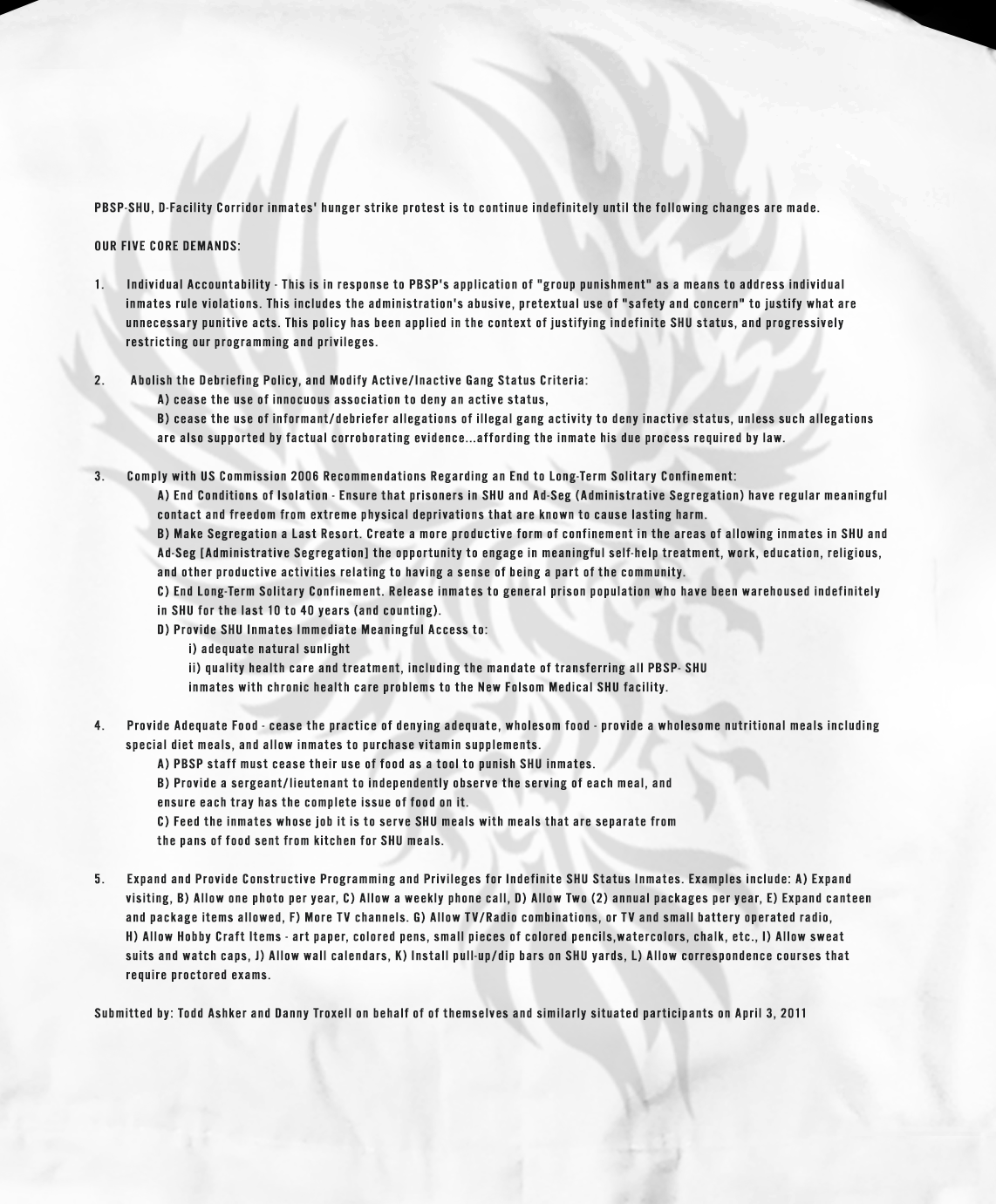

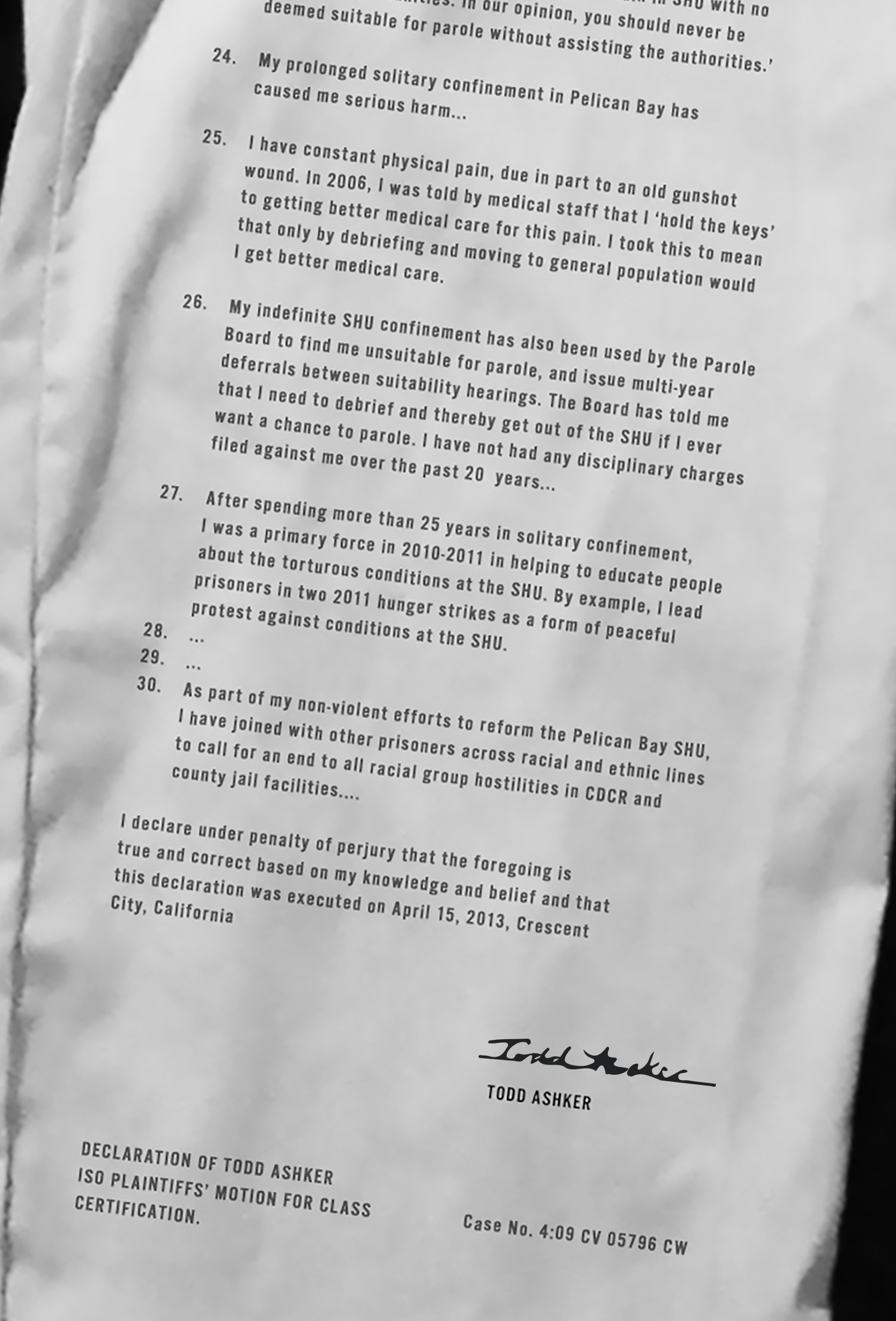

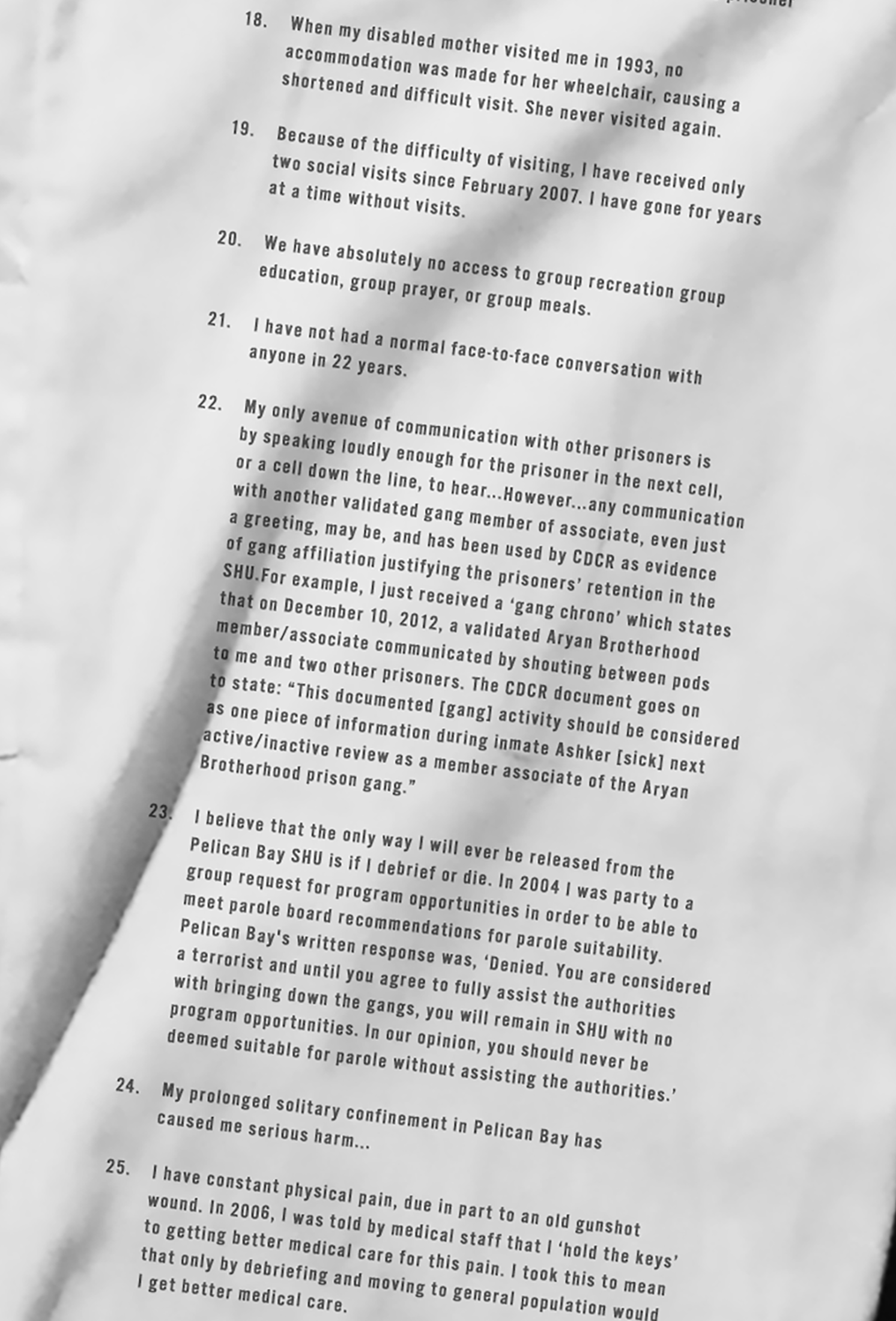

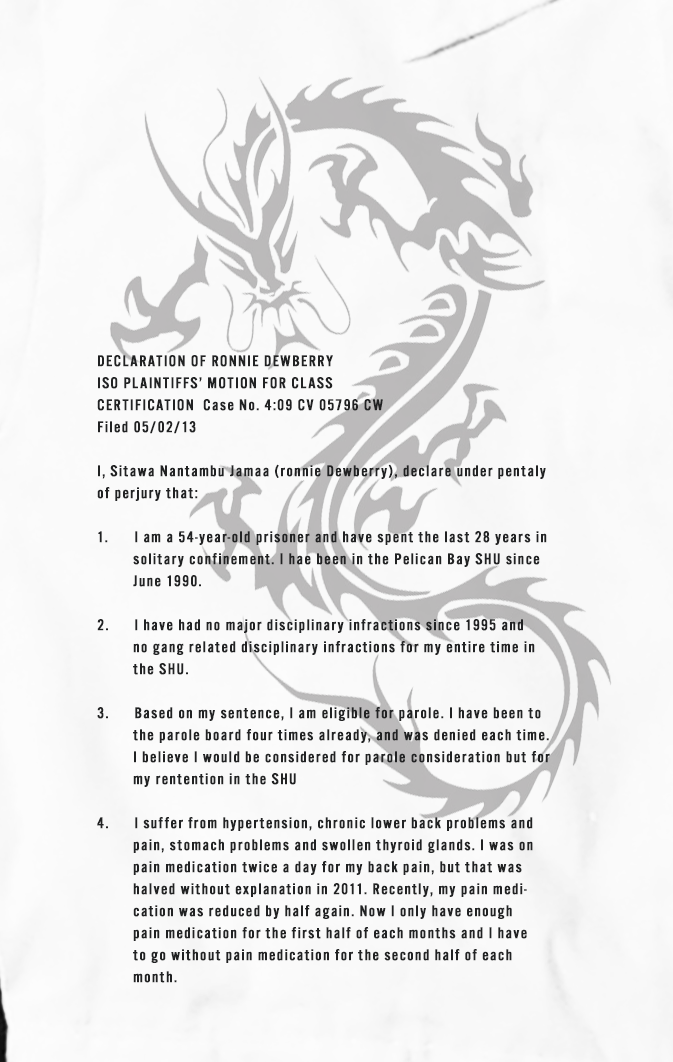

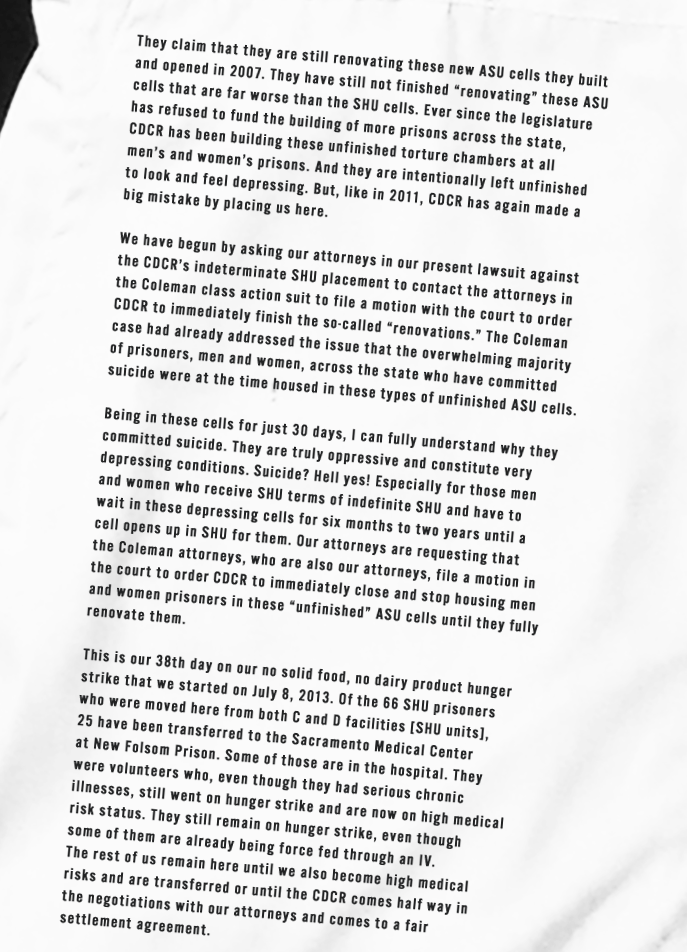

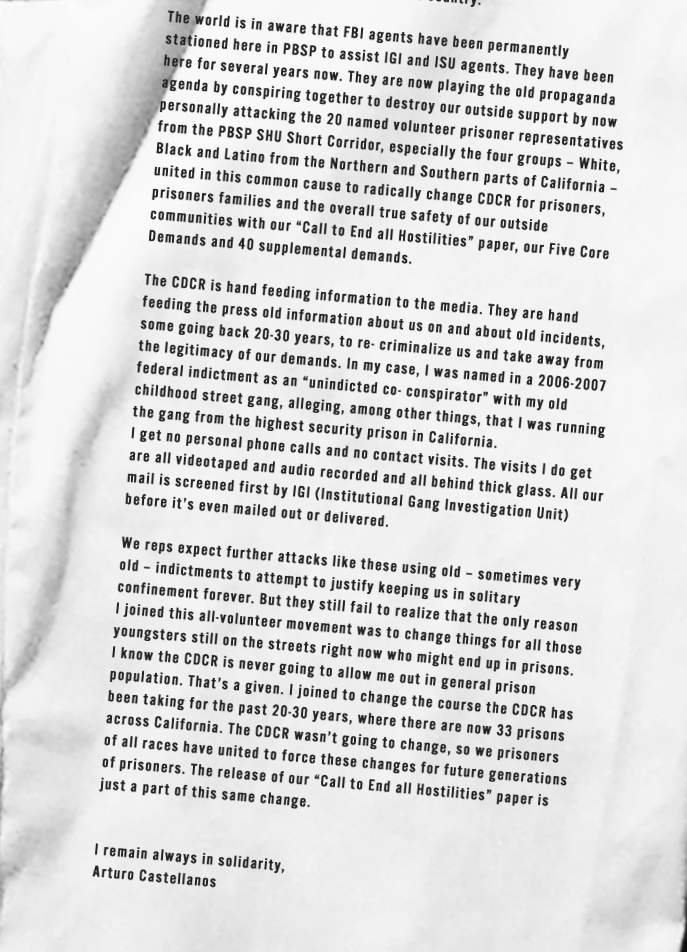

Ashker v. Governor of California was a federal class-action lawsuit on behalf of prisoners held in the Security Housing Unit (SHU) at California’s Pelican Bay State Prison who had spent a decade or more in solitary confinement. The case charged that prolonged solitary confinement violates the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment and that the absence of meaningful review for SHU placement violates the prisoners’ rights to due process. The legal action was part of a larger movement to reform conditions in SHUs in California’s prisons that was sparked by hunger strikes by thousands of SHU prisoners in 2011 and 2013; the named plaintiffs in Ashker include Todd Ashker, Jamaa Sitwaa, Arturo Castellanos, Lewis Powell and several other leaders and participants from the hunger strikes.

I was transferred to the Pelican Bay SHU on May 2, 1990, whereupon staff told me that I would be here until I paroled, died or debriefed. I’ve been here ever since. In 2004 I was party to a group request for program opportunities in order to be able to meet parole board recommendations for parole suitability. Pelican Bay's written response was, ‘Denied. You are considered a terrorist and until you agree to fully assist the authorities with bringing down the gangs, you will remain in SHU with no program opportunities. In our opinion, you should never be deemed suitable for parole without assisting the authorities.’

One of the first things gang unit staff ask a debriefer is, ‘Do you want to call your wife and family and tell them that you’re done and let them know they may be in danger?’ This threat is well established—many debriefers and their family members outside prison have been seriously assaulted and killed.

This attitude is in keeping with how prison staff view prisoners and their families. In 1992, my paraplegic mom traveled 400 miles to visit me. Visit staff told her she’d have to wheel herself to the SHU visiting area. Another visitor assisted her. The next day, staff hassled her for four hours before letting her in to visit. She never came back due to what happened. Over the years, I received two 10-minutes phone calls with her: one when my sister died in 1998 and one when my grandmother died in 2000. Pelican Bay staff told me many times that if I wanted to be transferred closer to my mom so I could see her, all I had to do was debrief. She has since passed away.

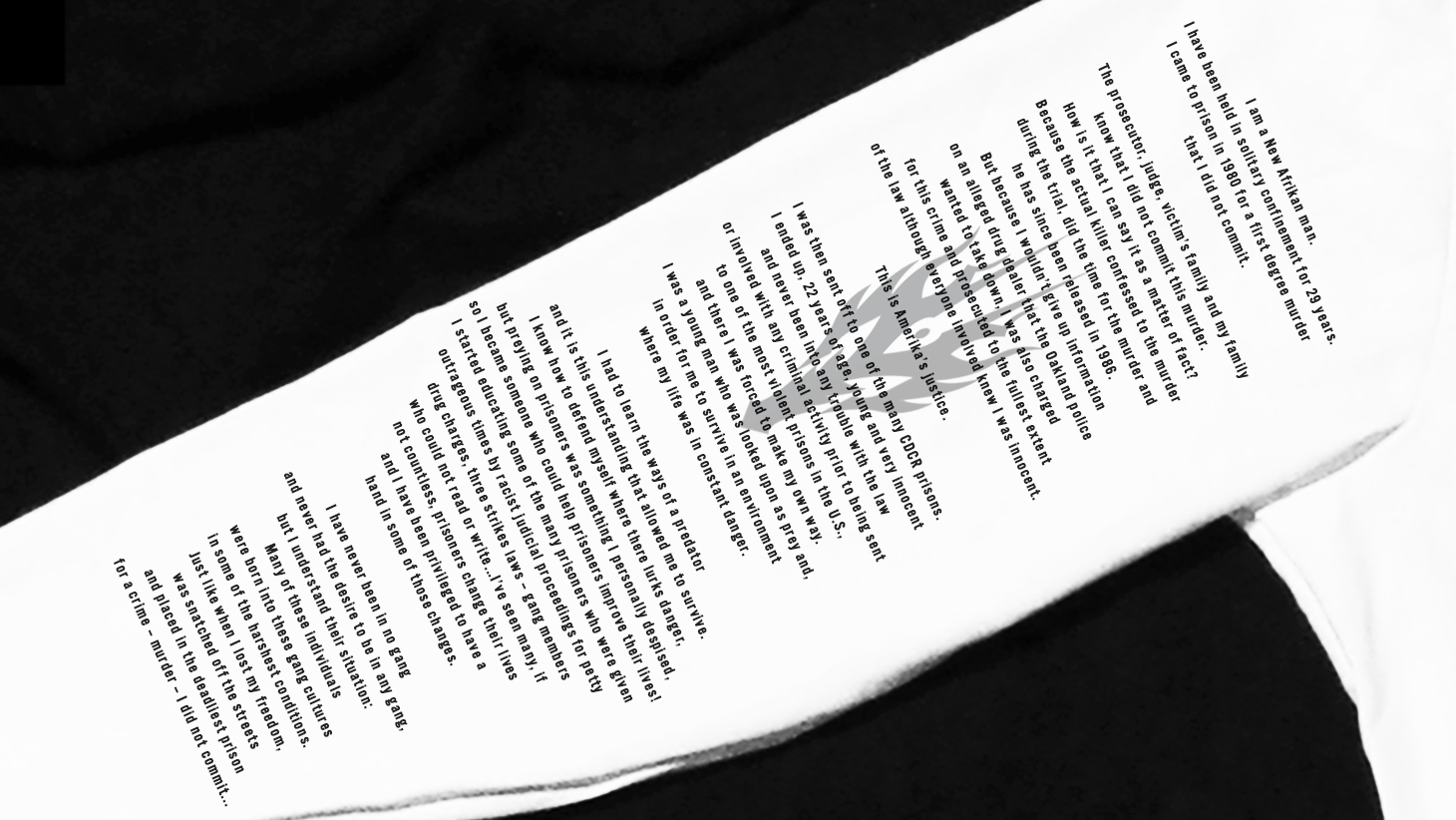

It is very important that you all clearly understand the depth of human torture to which I was subjected for 30-plus years by CDCr and CCPOA (California Prison Guards Union). I was placed in solitary confinement – the SHU – on May 15, 1985, on trumped-up, illegal and fabricated state documents. The torture was directed at me and similarly situated women and men prisoners held in California’s solitary confinement locations throughout CDCr, with the approval and sanctioning of California governors, CDCr secretaries and directors, attorneys general, along with the California Legislature for the past 40 years. They have allowed for their own citizens – prisoners – to suffer horrible crimes with their systematic process of physically and mentally killing prisoners for decades, with no regard for human life.

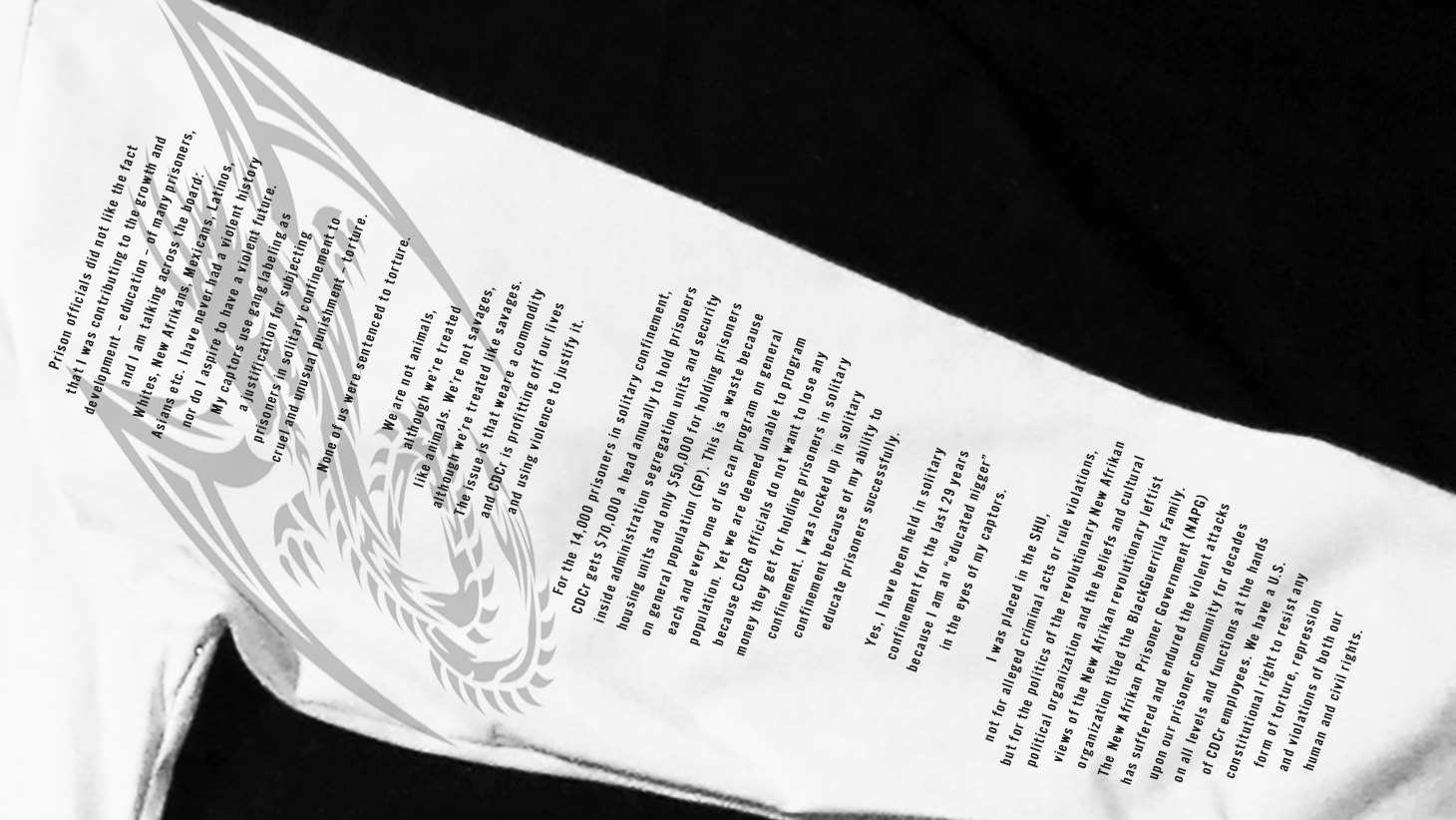

Two leading lieutenants removed me from San Quentin's general population, not for alleged criminal acts or rule violations, but for the politics of the revolutionary New Afrikan political organization and the beliefs and cultural views of the New Afrikan revolutionary leftist organization titled the Black Guerrilla Family (BGF).I was targeted by CDCr prison officials at San Quentin during 1983 on up until I was removed from the general population (GP) and housed in San Quentin’s Control Units within their solitary confinement housing building, North Housing Unit (NHU). The sole reason for my housing there was that I was educating all New Afrikan prisoners on San Quentin’s GP about our rich New Afrikan history behind California prison walls and across the United States.

I was teaching them that we as a people shall not be forced to deny ourselves the rights in the U.S. Constitution and the California Constitution. Yes, I personally believe that every New Afrikan woman and man has the right to protest any CDCr Jim Crow or Black Code-type rules or laws which violate our human rights as a person or prisoner.

And so I was educating my people to our civil rights and human rights in the California prison system during the 1980s while I was within the GP. I continued to educate my people, the New Afrikan nation, when I was placed in solitary confinement from 1983 to Oct. 11, 2015. It was a tragedy for three decades – yes, 30-plus years I was forced to suffer all forms of torture and witness killings of human life at the hands of CDCr officials and staff for decades, aided and abetted by governors, stakeholders, the Legislature, CDCr directors and secretaries, etc.

The New Afrikan Prisoner Government (NAPG) has suffered and endured violent attacks upon our prisoner community for decades on all levels and functions at the hands of CDCr employees. We have a U.S. Constitutional right to resist any form of torture, repression, and violations of both our human and civil rights.

I was placed in the SHU, not for alleged criminal acts or rule violations, but for the politics of the revolutionary New Afrikan political organization and the beliefs and cultural views of the New Afrikan revolutionary leftist organization titled the Black Guerrilla Family (BGF).

I shall not be found among the broken men and women! I shall live and die a warrior for our New Afrikan Nation and humanity!

Sitawa Nantambu Jamaa

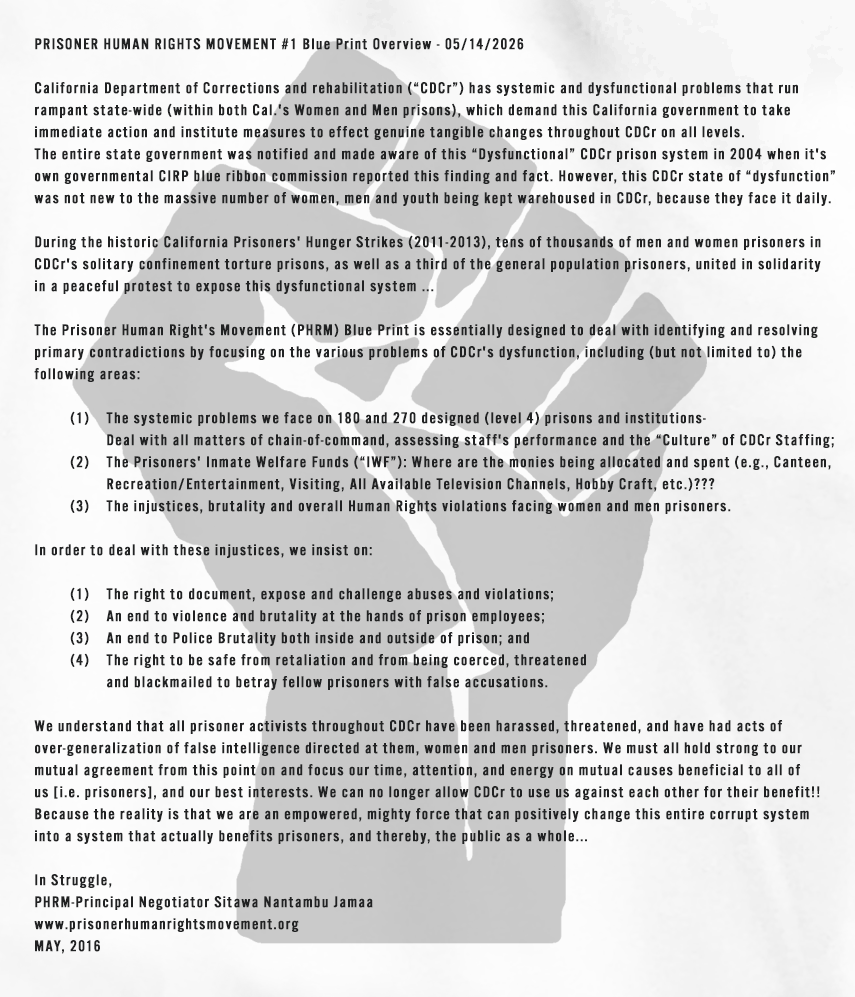

Oct 14, 2017 marked the 2 year anniversary of the approval of the Ashker settlement. We believe that CDCR is still engaged in constitutional violations that deny prisoners due process and seeks to put us back in the hole, for many, indeterminately under the guise of Administrative SHU. We must stand together, not only for ourselves, but for future generations of prisoners, so that they don’t have to go through the years of torture that we had to. We need all prisoners – young and old -to make our collective outcry public to ensure that the victory that we have won is not reversed by CDCR behind closed doors.

Ultimately, we are the ones who are responsible for leading the struggle for justice and fair treatment of prisoners. That is why we entered into the historic Agreement to End Hostilities, and why it is so important that the prisoner class continue to stand by and support that agreement. We cannot allow our victories to be nullified by CDCR’s abuse of power, and may have to commit ourselves to non-violent peaceful struggle if CDCR continues on its present path.

Our attorneys will seek an extension of the agreement due to CDCR’s systemic violations of the constitution. We don’t know what the court will do, but we do know that prisoners and their families have to re-energize our human rights movement to fight against the continuing violations of our rights. Examples are:

CDCR’s continued misuse of Confidential Information to place prisoners back in the SHU, particularly with bogus conspiracy charges;

- The lack of out of cell time, programming and vocational programs in Level 4 prisons. The last letter of CDCR stands for rehabilitation, and there is almost no rehab programs and opportunities in the level 4 prisons. They function like modified SHUs;

- The denial of parole to lifers and Prop 57 prisoners who have clean records simply because of old, unconstitutional gang validations and CDCR’s illegally housing us in SHU for years;

- The turning of the Restrictive Custody General Population Unit which was supposed to be a GP unit where prisoners who had real safety concerns could transition to regular GP, into a purgatory where the only way out is to either debrief or die;

- CDCR promulgation of new regulations which gives the ICC discretion to put people back in the SHU, allows for many prisoners to be placed in the future in indeterminate Administrative SHU, or to be placed in the RCGP on phony safety concerns.

taken from Statement of Prisoner Representatives on Second Anniversary of Ashker v. Brown Settlement

October 13, 2017 - By Todd Ashker, Sitawa Nantambu Jamaa, Arturo Castellanos, and George Franco

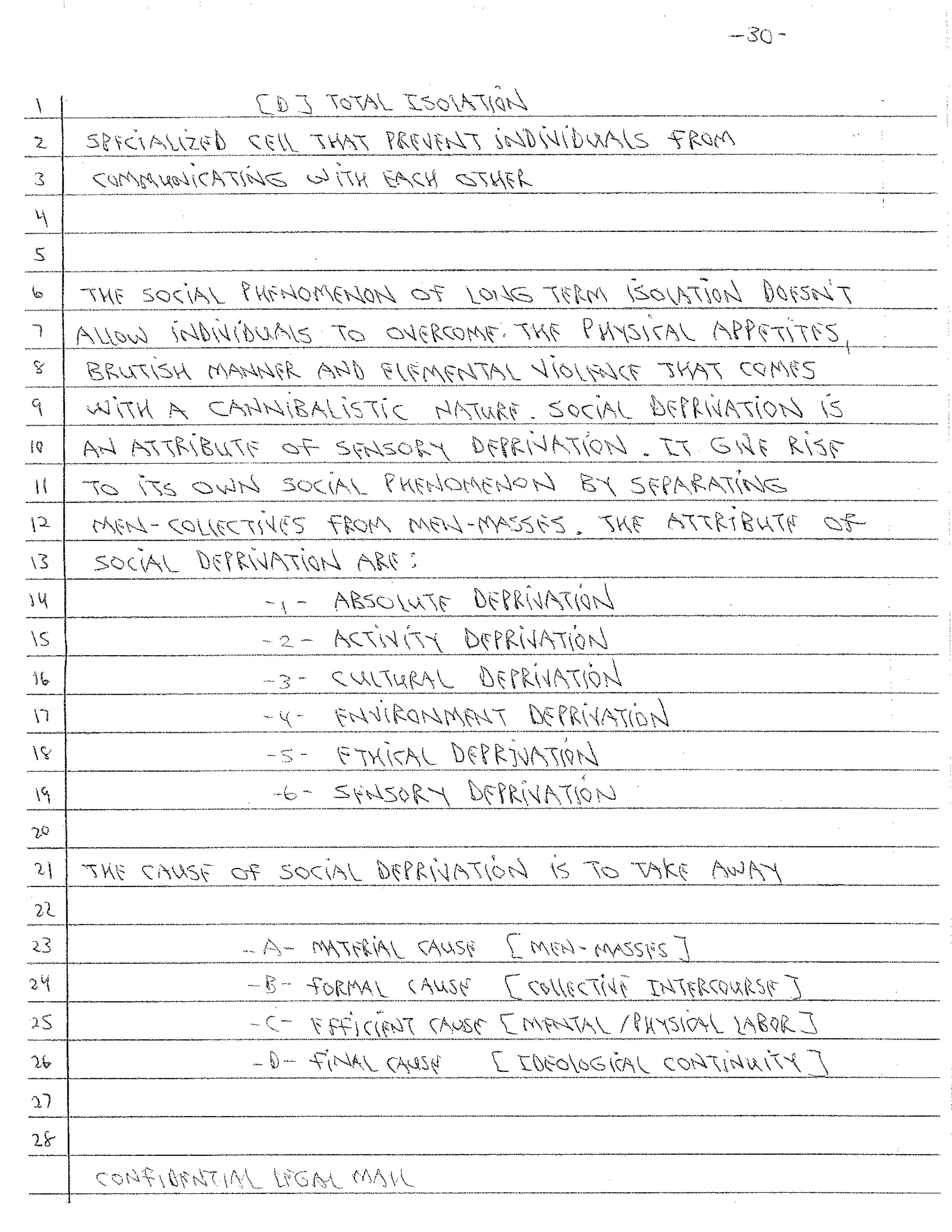

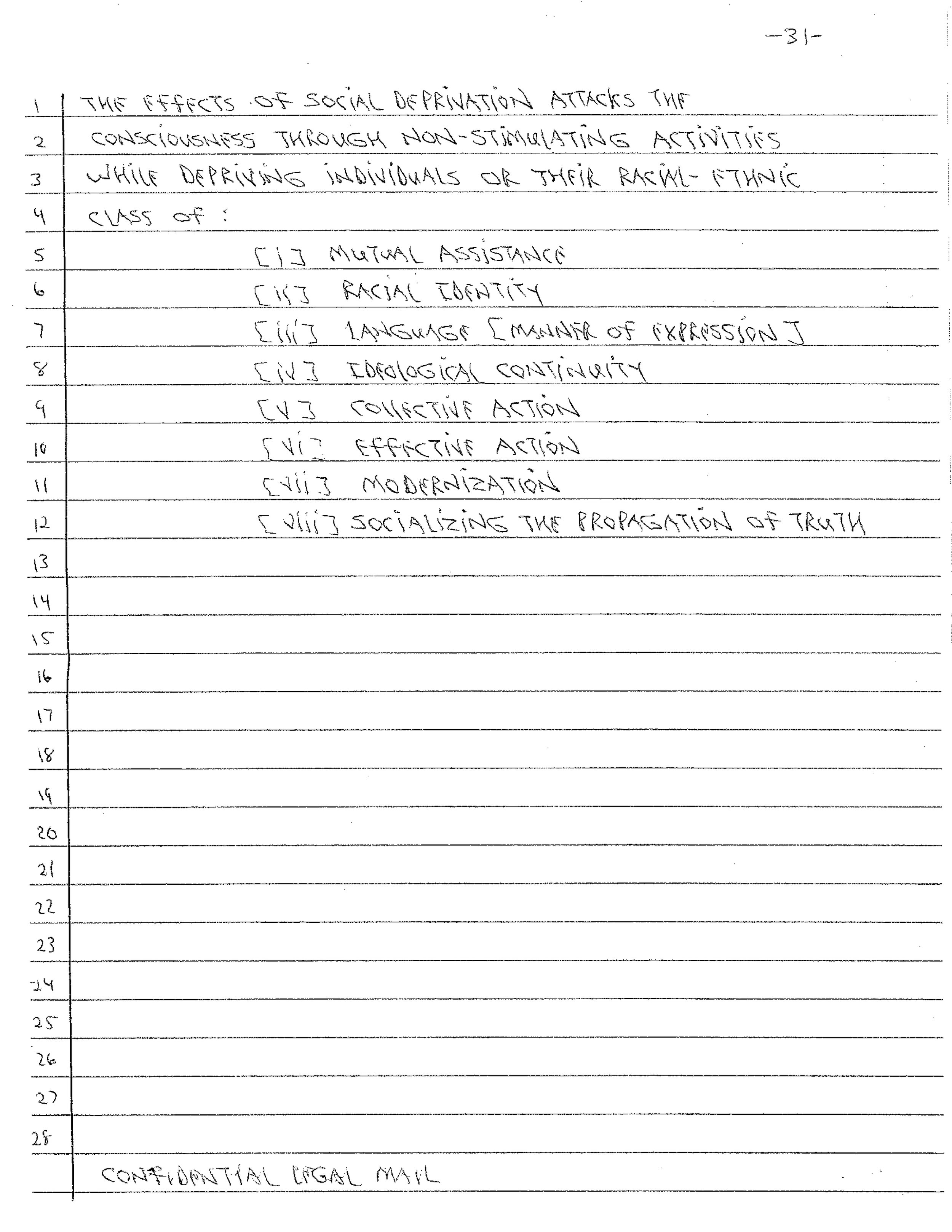

Louis Powell, a member of the Pelican Bay State Prison SHU short-corridor collective group that initiated the 2011 and 2013 hunger strikes, has been incarcerated in California State Prisons since 06/20/1986. He is 67 years old. He was eligible for parole in September, 1999. He is now locked up in the California State Prison at Lancaster. He is the co-author of many statements published by the short corridor collective and the hand-written document, THE OPTIMUM ATTRITION: AN ESSAY ON SENSORY DEPRIVATION, published, in part, below.

This settlement represents a monumental victory for prisoners and an important step toward our goal of ending solitary confinement in California, and across the country...

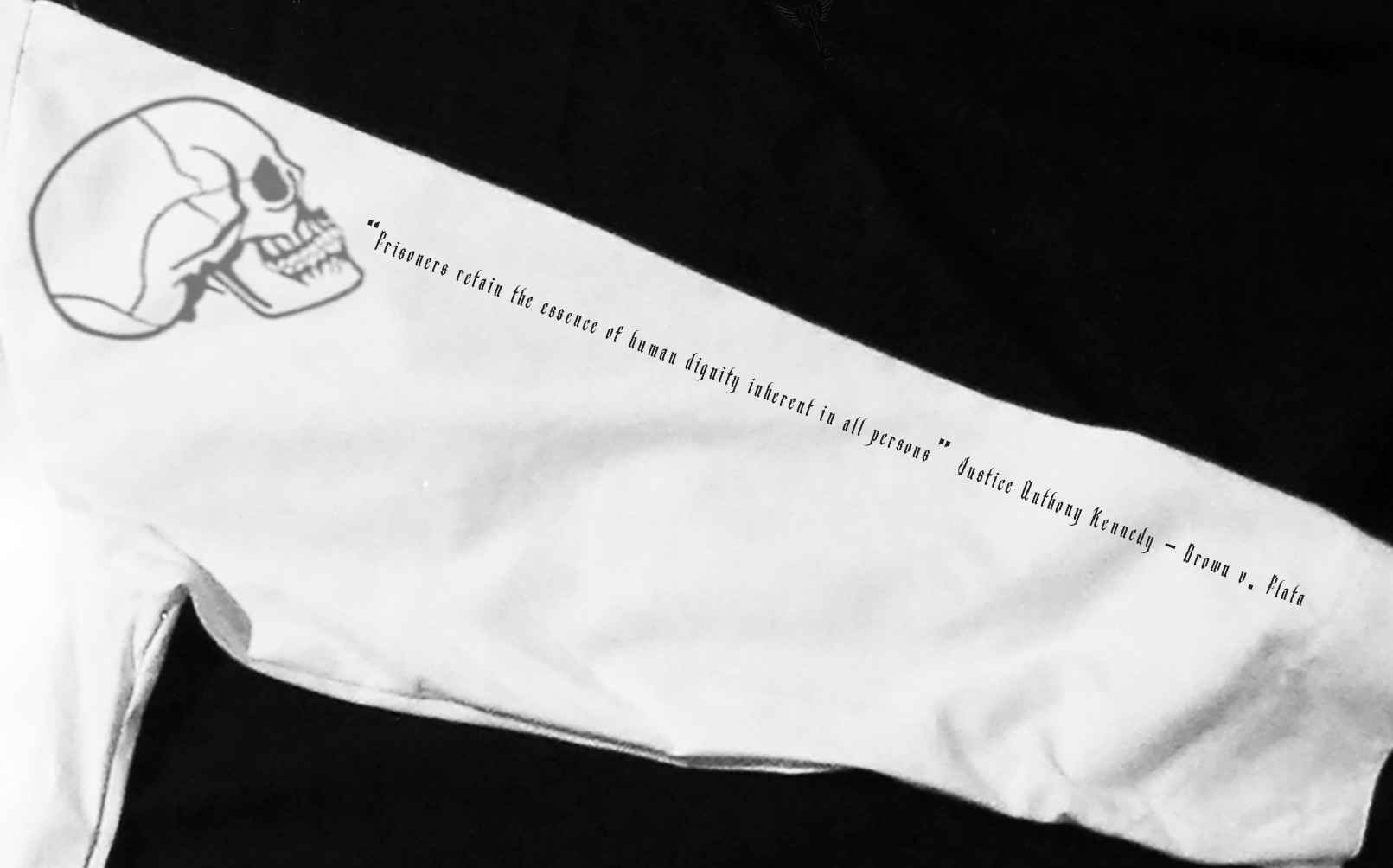

This victory was achieved by the efforts of people in prison, their families and loved ones, lawyers, and outside supporters. Our movement rests on a foundation of unity: our Agreement to End Hostilities. It is our hope that this groundbreaking agreement to end the violence between the various ethnic groups in California prisons will inspire not only state prisoners, but also jail detainees, county prisoners and our communities on the street, to oppose ethnic and racial violence. From this foundation, the prisoners’ human rights movement is awakening the conscience of the nation to recognize that we are fellow human beings. As the recent statements of President Obama and of Justice Kennedy illustrate, the nation is turning against solitary confinement. We celebrate this victory while, at the same time, we recognize that achieving our goal of fundamentally transforming the criminal justice system and stopping the practice of warehousing people in prison will be a protracted struggle. We are fully committed to that effort, and invite you to join us.

Todd Ashker

Sitawa Nantambu Jamaa

Luis Esquivel

George Franco

Richard Johnson

Paul Redd

Gabriel Reyes

George Ruiz

Danny Troxell

Oct 14, 2017 marks the 2 year anniversary of the approval of the Ashker settlement. However, unfortunately our general monitoring is due to run out after two years unless the Court grants an extension. We believe that CDCR is still engaged in constitutional violations that deny prisoners due process and seeks to put us back in the hole, for many, indeterminately under the guise of Administrative SHU.

Our attorneys will seek an extension of the agreement due to CDCR’s systemic violations of the constitution. We don’t know what the court will do, but we do know that prisoners and their families have to re-energize our human rights movement to fight against the continuing violations of our rights. Examples are:

CDCR’s continued misuse of Confidential Information to place prisoners back in the SHU, particularly with bogus conspiracy charges;

The lack of out of cell time, programming, and vocational programs in Level 4 prisons. The last letter of CDCR stands for rehabilitation, and there is almost no rehab programs and opportunities in the level 4 prisons. They function like modified SHUs;

The denial of parole to lifers and Prop 57 prisoners who have clean records simply because of old, unconstitutional gang validations and CDCR’s illegally housing us in SHU for years;

The turning of the Restrictive Custody General Population Unit which was supposed to be a GP unit where prisoners who had real safety concerns could transition to regular GP, into a purgatory where the only way out is to either debrief or die;

CDCR promulgation of new regulations which gives the ICC discretion to put people back in the SHU allows for many prisoners to be placed in the future in indeterminate Administrative SHU or to be placed in the RCGP on phony safety concerns.

We must stand together, not only for ourselves but for future generations of prisoners, so that they don’t have to go through the years of torture that we had to. We need all prisoners – young and old -to make our collective outcry public to ensure that the victory that we have won is not reversed by CDCR behind closed doors. Ultimately, we are the ones who are responsible for leading the struggle for justice and fair treatment of prisoners. That is why we entered into the historic Agreement to End Hostilities, and why it is so important that the prisoner class continue to stand by and support that agreement. We cannot allow our victories to be nullified by CDCR’s abuse of power and may have to commit ourselves to non-violent peaceful struggle if CDCR continues on its present path.

We need everyone - prisoners, their families, and the public - to send comments on CDCR’s proposed regulations to staff@aol.ca.gov, send emails and letters urging Gov. Brown to sign Assembly Bill 1308, make sure that prisoner complaints about unfair treatment are publicized, and to work together to rebuild our prisoners’ human rights movement.

We cannot let CDCR increase its use of prolonged solitary confinement either by misusing confidential information to place prisoners in SHU on phony conspiracy charges or through increasing the use of Administrative SHU. As the Supreme Court stated over one hundred years ago in the 1879 case of Wilkerson v. Utah, it is “safe to affirm that punishment of torture… and all others in the same line of unnecessary cruelty are forbidden by that [the Eighth] Amendment.” The admired historian Howard Zinn noted the application of that decision to the modern SHU: “All we need then, is general recognition that to imprison a person inside a cage, to deprive that person of human companionship, of mother and father and wife and children and friends, to treat that person as a subordinate creature, to subject that person to daily humiliation and a reminder of his or her own powerlessness in the face of authority… is indeed torture and thus falls within the decision of the Supreme Court a hundred years ago.”

Court's decision on Plaintiffs in Ashker v. Brown seeking relief from ongoing isolation

On March 29, 2018, a federal magistrate judge in California held that prisoners in a class-action lawsuit over long-term solitary confinement, who entered into a settlement agreement with the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), had not proven a material breach of the agreement. That decision was subsequently overruled in part by the district court.

CDCR prisoners held in Secure Housing Units (SHUs) stay on lockdown 23 hours a day and have limited programming opportunities or privileges. A large number of those prisoners have remained in SHUs for years or even decades due to alleged gang affiliations.

On behalf of a class of prisoners in administrative SHU, California state prisoner Todd Ashker and other plaintiffs entered into a September 2015 settlement with the CDCR that included a requirement that all class members eligible for release under the agreement would be transferred to a “General Population-level IV 180-design facility, or other general population institution consistent with [their] case factors.” [See: PLN, Nov. 2016, p.1; Oct. 2014, p.30].

The CDCR transferred over 200 SHU prisoners to other facilities, where in some cases conditions were no better than in segregation units. Many class members asserted they did not receive even one hour a day of out-of-cell time, did not receive the agreed programming, and actually lived in more punitive and isolated circumstances than before. The prisoners filed a motion for enforcement, arguing the CDCR had violated the spirit of the settlement agreement; they relied on surveys from class members and expert declarations as evidence.

The CDCR countered that the surveys were unreliable, that only 55 surveys had been answered out of 205 sent – skewing the results – and that the plaintiffs’ experts did not conduct a separate investigation to verify the survey data.

The magistrate judge over the case held the prisoners had incorrectly relied upon their interpretation of “General Population Level IV 180-design facilities,” which was not otherwise defined in the settlement.

“Not only does the Settlement Agreement not specify details as to the conditions of confinement for class members transferred to a General Population-level IV 180-design facility, it provides no requirements regarding the conditions of such a facility as compared with general population facilities nation-wide, or as compared with other inmates in the CDCR systems,” the magistrate judge wrote.

Accordingly, the prisoners’ motion for enforcement of the settlement was denied. They sought de novo review by the district court, and on July 3, 2018, the court granted their motion “to the extent that Plaintiffs must receive more out-of-cell time than they received in the Pelican Bay SHU. They should receive out-of-cell time consistent with the CDCR’s regulations and practices with respect to Level IV general population inmates, as well as its constitutional obligations.”

The case remains pending. See Ashker v. Brown, U.S.D.C. (N.D. Cal.), Case No. 4:09-cv-05796-CW.

SHU-shifting update: Relief finally granted to California prisoners experiencing ongoing isolation. On July 3, a critical ruling issued in Ashker v. Brown (aka Ashker v. Governor, Docket No. 4:09-cv-09-5796 CW (N.D. Cal.)), the federal class-action lawsuit challenging indefinite solitary confinement in California. The ruling, issued by Presiding Judge Claudia Wilken, granted Plaintiffs’ appeal on a motion challenging the ongoing conditions of extreme isolation endured by many class members.

The motion was initially filed with the court on Oct. 13, 2017, along with several other motions brought to enforce Plaintiffs’ settlement agreement with the CDCR. Plaintiffs contended that, contrary to the terms of the settlement agreement, many class members effectively remain isolated in restrictive housing facilities.

Oral argument on the motion was heard by Magistrate Judge Illman on Feb. 23, 2018, in a courtroom packed with human rights advocates and activists. Illman asked some good questions of both sides and appeared to grasp the issues raised by the Plaintiffs’ counsel. However, on March 29 he issued an order denying the motion, prompting Plaintiffs’ legal team to move for a de novo determination (new decision) before Presiding Judge Claudia Wilken.

The ruling, issued by Presiding Judge Claudia Wilken, granted Plaintiffs’ appeal on a motion challenging the ongoing conditions of extreme isolation endured by many class members.

The Ashker case specifically challenged the CDCR’s practices and policies of indefinitely confining prisoners at Pelican Bay State Prison’s SHU (so-called Security Housing Unit) on constitutional grounds. Through these practices and policies, Plaintiffs asserted, the CDCR had violated both the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment and the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of due process.

Some 78 individuals, they alleged, had been incarcerated in Pelican Bay’s SHU for decades on end. And, more than 500 had been there for at least 10 years. All of these people spent around 22½ hours or more each day cramped in closet-sized cells. Any yard time they received occurred within the narrow confines of an indoor concrete-walled pen or “dog run.” Any visits with loved ones took place from either side of a glass partition breached only by a telephone line.

This was merely on account of the fact that the CDCR had deemed them “associates” or members of prison gangs. In other words, no misconduct much less criminal activity was required of class members to keep them isolated on an indefinite basis.

On Sept. 1, 2015, a settlement agreement was reached in the case. (The agreement was tentatively approved by the court on Oct. 14, 2015, and received the court’s final approval on Jan. 26, 2015.)

Those affected by the agreement include “all prisoners who have now, or will have in the future, been imprisoned in Pelican Bay’s SHU for 10 or more years.” Also affected is a subset of such prisoners, who were moved from Pelican Bay’s SHU to a SHU at another prison before the case settled. Together, both groups of prisoners comprise the settlement class.

Following the settlement, the CDCR released over 1,400 and up to around 1,500 class members retained in its SHUs statewide into lower-security facilities. This was pursuant to paragraph 25[iii] of the settlement agreement. Yet, although paragraph 25 has been complied with on paper, Plaintiffs’ motion and subsequent appeal raised the question, has compliance been substantively achieved?

Plaintiffs’ motion filed Oct. 13, 2017

As of Aug. 2017, according to CDCR data, 712 class members were housed in what are called “General Population Level IV 180-design” (maximum-security) facilities. Plaintiffs’ attorneys however contended that many class members were getting even less out-of-cell time than they experienced while in SHU. In support of their contention, they pointed to the results of a survey they conducted in around March 2017.

Fifty-five class members housed in various Level IV facilities completed the survey, tracking the amount of out-of-cell time they received during a one-month period. Sixteen of these 55 respondents reported getting an average of less than one hour of out-of-cell time per day. Another 11 reported getting an average of less than two hours per day.

And, a total of nine respondents reported not leaving their cells at all on most days. That is, they spent anywhere from 16 to 25 days locked in their cells during the one-month tracking period, without access to the yard, face-to-face contact, showering facilities, etc.

In declarations filed with Plaintiffs’ initial enforcement motion, eight class member-respondents elaborated on the conditions they endure in Level IV facilities. One such prisoner swore: “The conditions … are similar to SHU, and my experience is likewise similar. I have limited social interaction and intellectual stimulation. I rarely go outside. It is difficult to find productive uses for my time.

“I have difficulty maintaining relationships with my family, especially since my ability to use the telephone is so infrequent and irregular. I suffer from insomnia. I suffer from anxiety that I feel is directly linked to the irregular programming: I am anxious because I do not know what will happen next.”

“The conditions … are similar to SHU, and my experience is likewise similar. I have limited social interaction and intellectual stimulation. I rarely go outside. It is difficult to find productive uses for my time.”

And, another prisoner testified: “The inconsistency of the programming … has left me anxious and frustrated. It is difficult to adapt and plan when I do not know what will happen the next day.

“Sometimes, to cope with the lack of stability, I tell myself, ‘The only program is no program,’ so I do not prepare physically and mentally to leave my cell only to suffer frustration and disappointment when it is canceled. But this means I am often not prepared for out-of-cell time when it is permitted.”

Feb. 23, 2018, hearing before Magistrate Judge Illman

During oral argument on Feb. 23, attorney Jules Lobel[iv] spoke on behalf of the plaintiffs. Lobel emphasized in his opening remarks that, although the CDCR says people have been moved into the general population, this doesn’t make it so: “General population” has to have an objective definition, he maintained.

When the magistrate asked him whether certain restrictions, such as restrictions on yard time, come with Level IV confinement, Mr. Lobel replied yes. But, this cannot mean restrictions of the magnitude that a significant number of class members are experiencing, he continued.

Although the CDCR says people have been moved into the general population, this doesn’t make it so: “General population” has to have an objective definition, he maintained.

The CDCR itself, he pointed out, previously avowed in court that people in the general population receive 10 hours of yard per week. But, nobody is getting 10 hours.

Adriano Hrvatin, for the state, countered that class members are being treated like “any other [Level IV] prisoner,” and they don’t want to be treated like other prisoners “anymore.” Hrvartin further argued that no remedy was possible for the affected class members that wouldn’t also involve the tens of thousands of people held in Level IV at large.

Implicit in Hrvatin’s arguments was the suggestion that, regardless of the CDCR’s prior avowals, Level IV prisoners receive the same amount of out-of-cell time as SHU prisoners. This point was not lost on Magistrate Illman: Illman quipped, could he expect a new class-action lawsuit concerning the conditions of Level IV confinement to be sent to him?

Magistrate Judge Illman’s March 29 order denying motion

In deciding Plaintiffs’ initial motion, Magistrate Judge Illman opined: “The Settlement Agreement which Plaintiffs signed provides for transfer of a specific subgroup of class members to a General Population Level IV 180-design facility within the CDCR system. It provides no details regarding the conditions of confinement for those class members.

“This is because, as Defendants argue, this case does not concern general population [sic]. Rather, it concerns CDCR’s agreement to change its segregated housing practices to comport with the related shift to a behavior-based model for managing prison gang affiliates.”

“It is undisputed that the class members at issue in this motion were each transferred to such a facility,” Illman pronounced in denying the motion.

Illman’s facile assessment struck this writer as being in stunning disregard for, or insensible to, Plaintiffs’ plea for substantive relief under the Eighth Amendment. It was equally heedless of paragraph 61 of the settlement agreement, which requires that the agreement be “construed as a whole, according to its fair meaning.” (Of paragraph 61, more will be said in a moment.)

While the Ashker case and settlement agreement do not concern the general population or conditions of confinement in general-population facilities, this is beside the point. Plaintiffs affirmatively claimed in their lawsuit that their indeterminate retention in restrictive conditions, including their isolation in cramped cells for 22½ –24 hours each day, constitutes cruel and unusual punishment. Moreover, the settlement agreement they entered into was intended to settle all of their claims.[v]

Plaintiffs’ motion for de novo determination

Relevant to both Plaintiff’s initial motion and their subsequent appeal from Illman’s March 29 order is the court’s observation made in an earlier ruling in the case last summer: “The parties’ agreement here is governed by California law (Settlement Agreement ¶ 60), which requires that contractual terms ‘be understood in their ordinary and popular sense, rather than according to their strict legal meaning …. Moreover, the parties agreed that ‘the language in all parts of this Agreement shall in all cases be construed as a whole, according to its fair meaning.’ (Settlement Agreement ¶ 61.).”

Plaintiffs repeatedly asserted in their briefings that many class members are not actually in what may be called general-population housing, within the ordinary or popular sense. Instead, they are in a form of restrictive housing.

As Plaintiffs’ legal team put it in their request for a de novo determination, “The defining distinction between general population and restrictive housing is time out of cell.” Likewise, restrictive housing is commonly understood (by the American Correctional Association and the Department of Justice, e.g.) to be “an environment where prisoners spend more than 22 hours a day locked in their cell.” The CDCR itself, they further remarked, recognizes that “‘general population’ and ‘restrictive housing’ are mutually exclusive terms.”

Plaintiffs repeatedly asserted in their briefings that many class members are not actually in what may be called general-population housing, within the ordinary or popular sense. Instead, they are in a form of restrictive housing.

Thus, in denying Plaintiffs’ “de novo” motion, Magistrate Judge Illman “incorrectly interpreted the operative contractual term – i.e. ‘General Population Level IV 180-design facility, or other general population institution’ – to allow Defendants to engage in a semantic sleight-of-hand.” By which some prisoners placed in nominal general-population facilities are treated “as if they were in segregation, or worse.”

Illman additionally misconstrued the remedy sought by the motion, Plaintiffs’ attorneys said. “The motion does not attack Level IV prisons generally, and does not even cover all class members,” they emphasized. Rather, it is focused “solely on the subset of class members entitled to GP [general population] transfer but who are being confined in restrictive housing conditions, or worse.”

Presiding Judge Wilken’s order granting ‘de novo’ motion

On July 3, Presiding Judge Claudia Wilken issued an order stating in part: “Having considered the papers, the Court GRANTS Plaintiffs’ motion to the extent that Plaintiffs must receive more out-of-cell time than they received in the Pelican Bay SHU. They should receive out-of-cell time consistent with the CDCR’s regulations and practices with respect to Level IV general population inmates, as well as its constitutional obligations. …

“The Settlement Agreement was intended to remove Plaintiffs from detention in the SHU, where they were isolated in a cell for twenty-two and a half to twenty-four hours a day. Second Amended Complaint ¶¶ 3, 63. Plaintiffs may seek to enforce the Settlement Agreement under either paragraphs 52 or 53, which require Plaintiffs to show ‘current and ongoing violations’ of the Eighth Amendment or the Fourteenth Amendment on a systemic basis, or other substantial noncompliance with the terms of the Agreement. Settlement Agreement ¶¶ 52, 53. …

“Defendants are hereby ordered to meet and confer with Plaintiffs’ representatives and their counsel with the goal of presenting a proposed remedial plan for Court approval. The matter is referred to Magistrate Judge Illman to mediate the meet and confer. Absent agreement, the parties shall present their own respective proposed remedial plans.”

As to what a remedial plan may look like, that’s a good question. To identify the subset of class members covered by Wilken’s order will be a challenge will be no easy task; it has been well over a year since class members were surveyed as to the amount of out-of-cell time they received. But, that’s the least of the obstacles standing between the status quo and actual relief for affected class members.